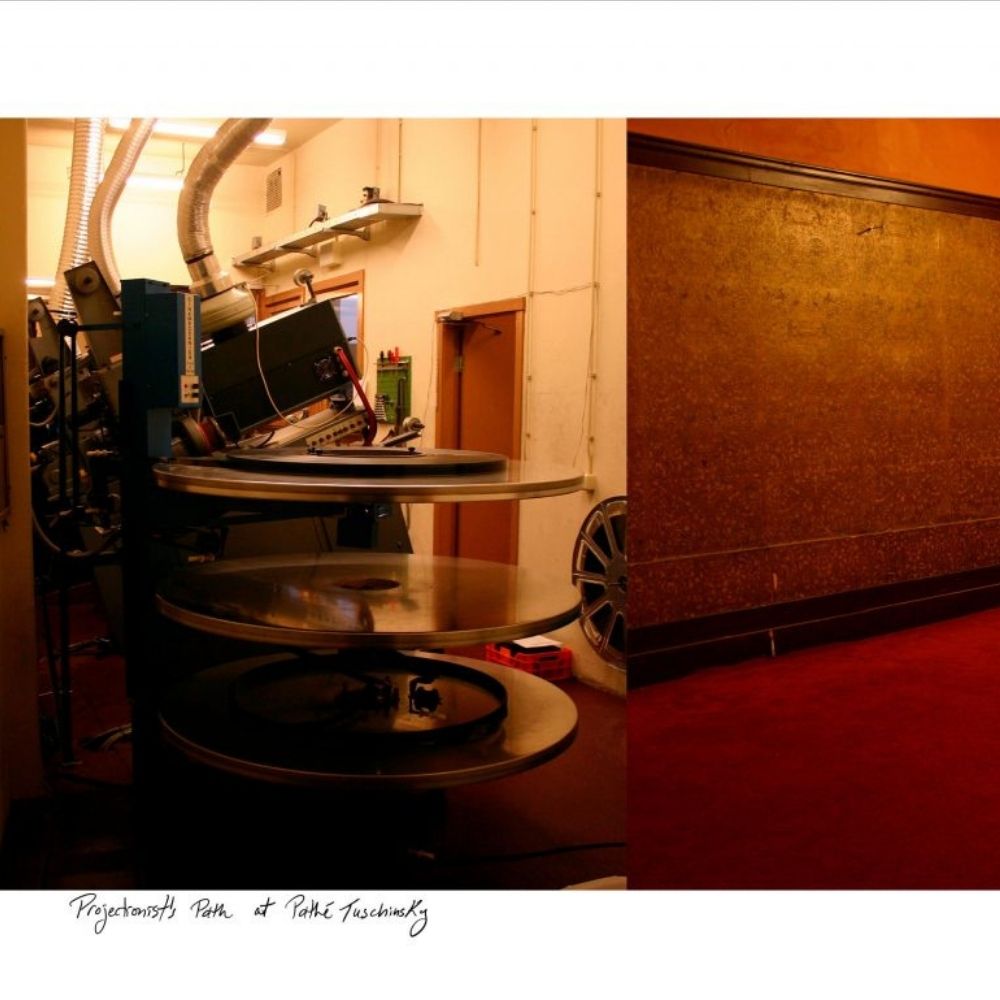

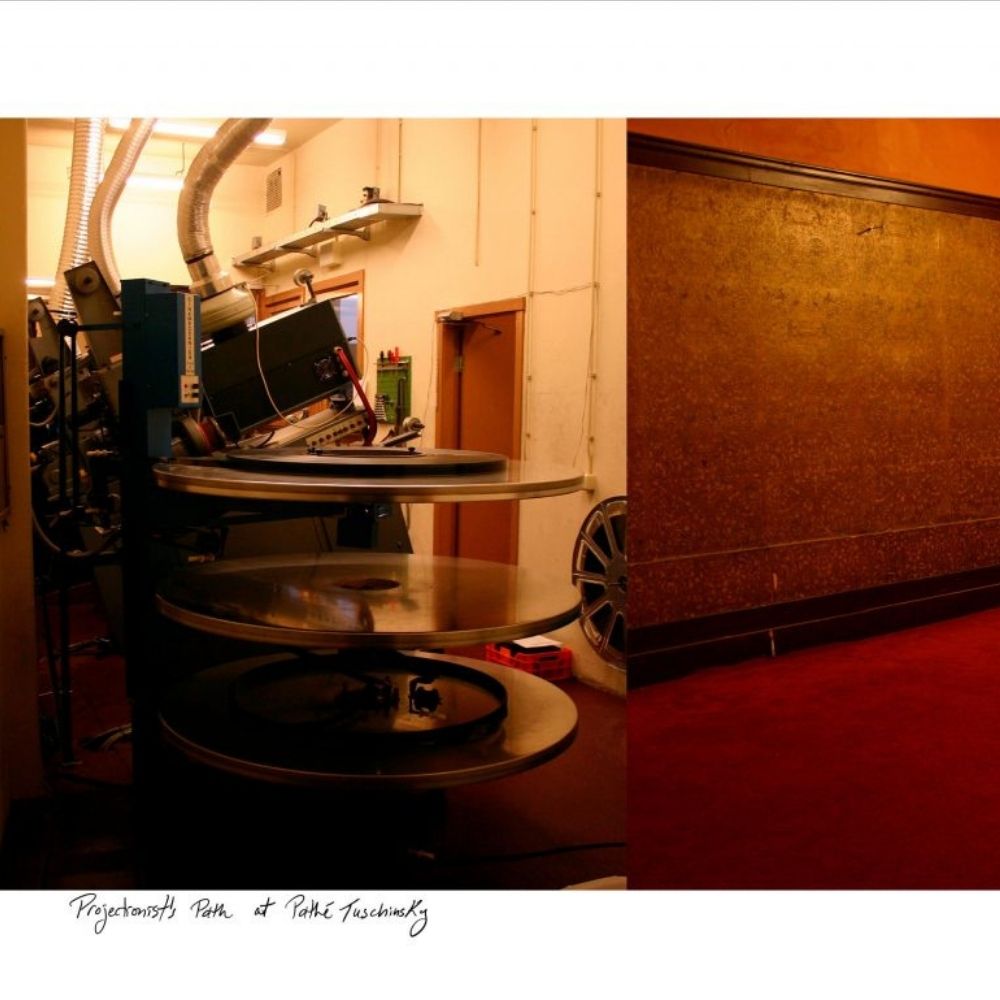

Last Days of Cinema: Projectionists's Path at Pathé Tuschinsky

Couldn't load pickup availability

Photograph printed on Epson Premium Lustre Photopaper (240gsm)

"Projectionist’s Path at Pathé Tuschinsky" is a part of “Last Days of Cinema,” a body of photographs and video works documenting the disappearance of celluloid projection in the face of digital technologies. Almost all major commercial movie theatres have now replaced their film projectors with digital projectors. In 2012, DCP (Digital Cinema Protocol) rapidly replaced 35mm film across North America. A domino effect took place when major distributors stopped releasing films on film, then theatres were forced to convert to DCP systems if they wanted to screen new films and, finally, a great number of major film processing labs closed their doors and ceased offering film processing services. Labs continue to scan film to digital, but now that the material object of the film print has become a rarity, the actual processing of film is a service that is becoming harder to find. 35mm celluloid film had been the standard for commercial movie projection from 1895 to 2012. Before the mass transition to DCP, many cinemas were still projecting film prints, while there was only a trickle of risk-takers and investors beginning to incorporate DCP into their theatres. It was during those last days, in 2008, as cinemas around the world were gradually replacing their film projectors with digital systems, that I was working as a projectionist at the Theatre Tuschinsky in Amsterdam.The photos and video footage in this project were shot when I worked as a projectionist in the ninety-year-old Theatre Tuschinsky in Amsterdam. The videos document my route from projection booth to projection booth, through both old and unrestored sections of the theatre as well as through fully modernized and computerized sections. The Tuschinsky Theatre was built in 1921, during the silent era of film, back when film was still a spectacle and going to the cinema was a special event — long before the days of DVD rentals, low resolution data projectors, and youtube videos. The Tuschinsky Theatre had five cinemas within it, as well as two bars, a kitchen, over 900 light fixtures, custom made carpets, embossed wallpapers, fountains, a VIP lounge, a bathroom designated for the royal family, and several custom-themed waiting rooms. Three of the five cinemas were restored for public use in 2002, and one of those three cinemas seats 800 people including the use of two balconies that wrapped around all the way to the screen with opera boxes. As a projectionist, it was a long and winding route from projection booth to projection booth, and it involved passing through many unrestored rooms, corridors, and hallways with torn wallpaper, graffiti, cracked walls, stained carpets, and random refuse. It was evident that these spaces were once resplendent, and by now they had become nothing more than a functional (if inefficient) route from one projection booth to another, which I walked (or ran) countless times a day as I loaded and unloaded movies throughout my shift at work. The video footage does not show any of the restored theatres, but focuses rather on the Theatre’s hidden spaces. A recurring image in this work is the scene from within the projection booth, where the image reflects back off the sound proof glass, thus casting an inverted reflection of the movie back onto the wall behind the projector. The projectionist often stands with her shadow cast within the inverted image of the movie. She is able to watch the audience watching the movie and her own image as a shadow cast within the movie behind her simultaneously.The photographs in this series focus on the empty spaces of the projection booths, back rooms, hallways, and other spaces that were inaccessible to the general public. The projection machinery, the platters, the reels of film, and the spaces themselves become the main characters in this project. These images allow the viewer’s gaze to wander through these hidden spaces, to caress forgotten objects, and to explore the architectural memory of this building.

Share

Shipping & Returns

General Shipping:

IOTA Studios offers free shipping on all orders over $100 within Canada, with the exception of framed artworks and sculptures.

International shipping rates are calculated upon checkout.

Packages are shipped by Canada Post.

Depending on size, prints are wrapped in with a stiffener, sealed in a plastic and shipped flat or carefully rolled in a sturdy box.

In the description of each artwork, it is specified whether it is digitally signed or hand signed.

Please reach out to iotastudiogallery@gmail.com for any specific shipping and handling questions. Orders ship within 10 business days.

Returns

If you have any issues with your artwork acquisition please email us at iotastudiogallery@gmail.com. We do not accept returns or exchanges. If your works arrive damaged, please notify us with images of the artwork within 14 days of delivery. Damaged digital prints will be replaced at the cost of IOTA, and in the case that a unique and irreplaceable artwork is damaged, IOTA will lead a claim process with shippers and the client will be offered a store credit or refund for the value of the artwork.

Public Display

Artwork purchased through IOTA Studio Gallery is not for public display. Canadian Artists' Representation/Le Front des artistes canadiens (CARFAC) sets presentation standards for Canadian artists, which require that artists be paid equitably for their work, including exhibitions. If the artwork is to be displayed publicly, or in an exhibition, IOTA Studios or the artist must be contacted directly to discuss presentation fees for the artist.